The GreyNoise Global Observation Grid observed active exploitation of two critical Ivanti Endpoint Manager Mobile vulnerabilities, and 83% of that exploitation traces to a single IP address on bulletproof hosting infrastructure that does not appear on widely circulated IOC lists. Meanwhile, several of the most-shared IOCs for this campaign show zero Ivanti exploitation in GreyNoise data. They are scanning for Oracle WebLogic instead. Defenders blocking only the published indicators may be watching the wrong door.

Why This Matters

The infrastructure actually conducting Ivanti EPMM exploitation at volume is an IP on a Censys-labeled "BULLETPROOF" autonomous system running simultaneous campaigns against four different software products. It is absent from the IOC lists many defenders adopted in the days after disclosure. The IOCs that are circulating point to shared VPN exit nodes conducting unrelated scanning and a compromised residential router with zero internet-wide activity. Organizations that relied solely on those indicators may have detection gaps against the exploitation GreyNoise is observing right now.

Key Takeaways

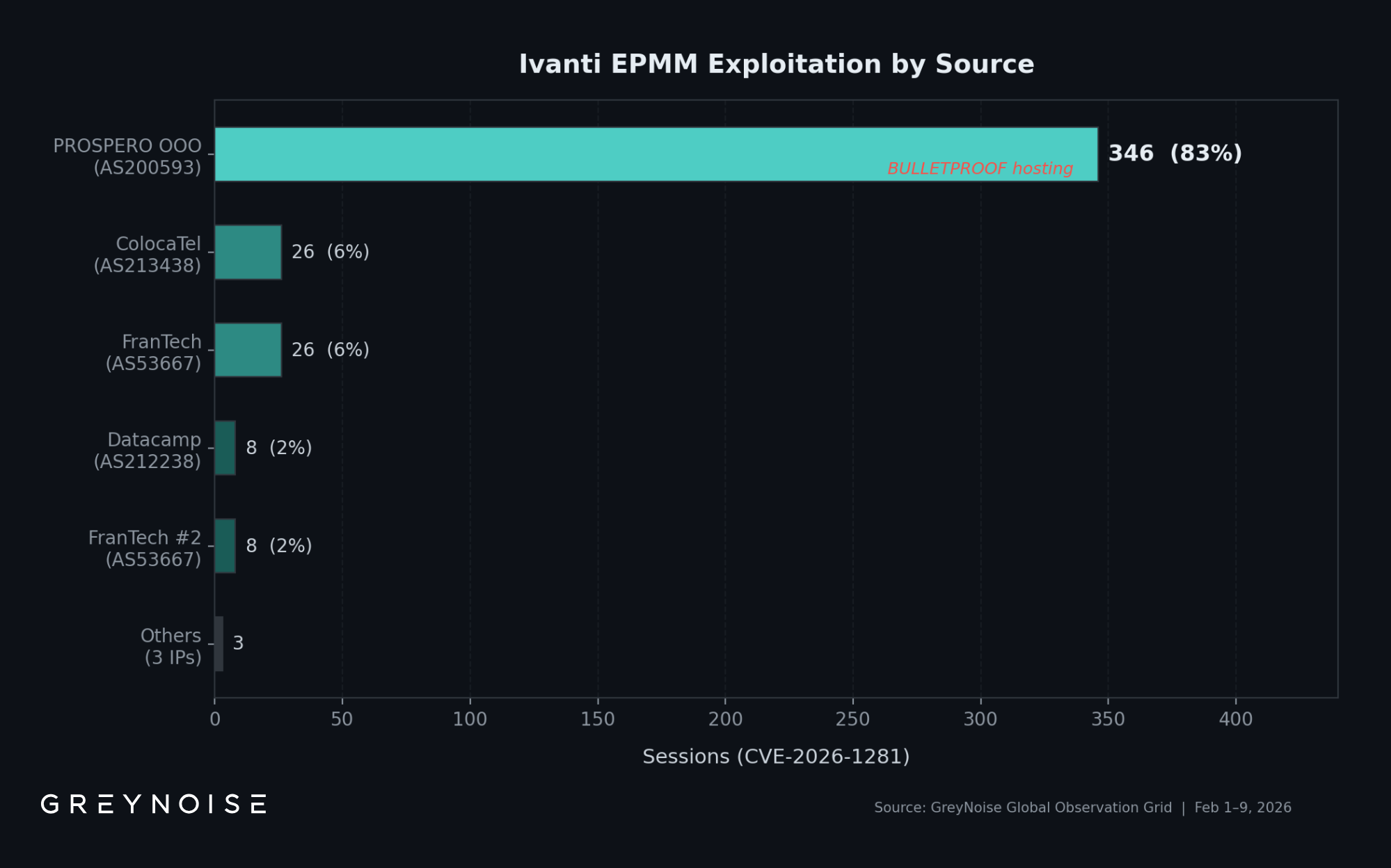

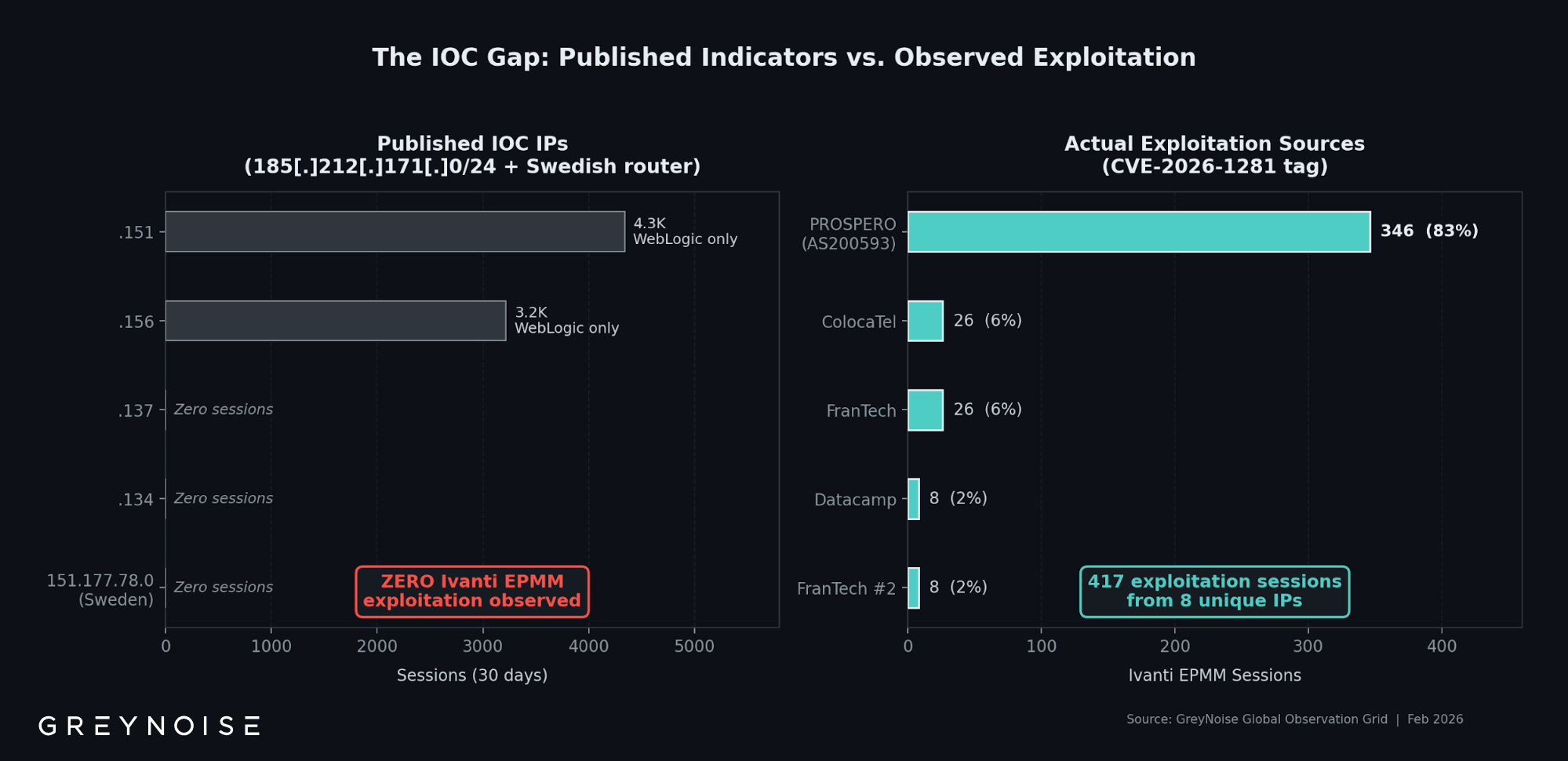

- Single dominant source. 83% of observed exploitation comes from one IP on bulletproof hosting (PROSPERO OOO, AS200593). This IP is not on widely published IOC lists, meaning defenders blocking only published indicators are likely missing the dominant exploitation source.

- Published IOCs show zero Ivanti activity. The /24 subnet containing four published Windscribe VPN IOC IPs generated 29,588 sessions in 30 days, with 99% targeting Oracle WebLogic on port 7001, not Ivanti. Zero Ivanti EPMM exploitation sessions from this range in GreyNoise data.

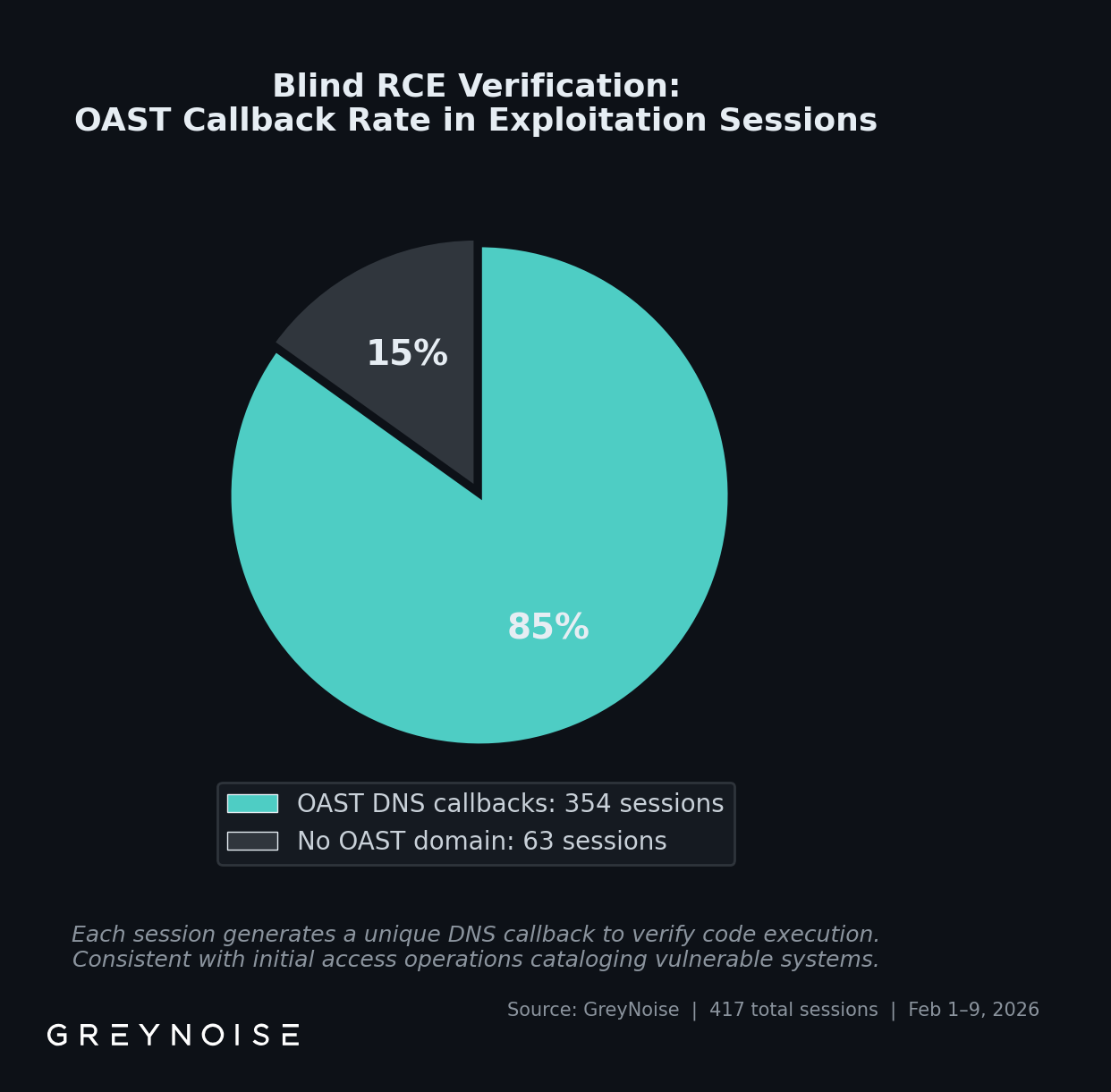

- Blind RCE verification, not immediate deployment. 85% of exploitation payloads use OAST DNS callbacks to verify command execution. This indicates a campaign cataloging vulnerable targets for later exploitation, consistent with initial access broker tradecraft.

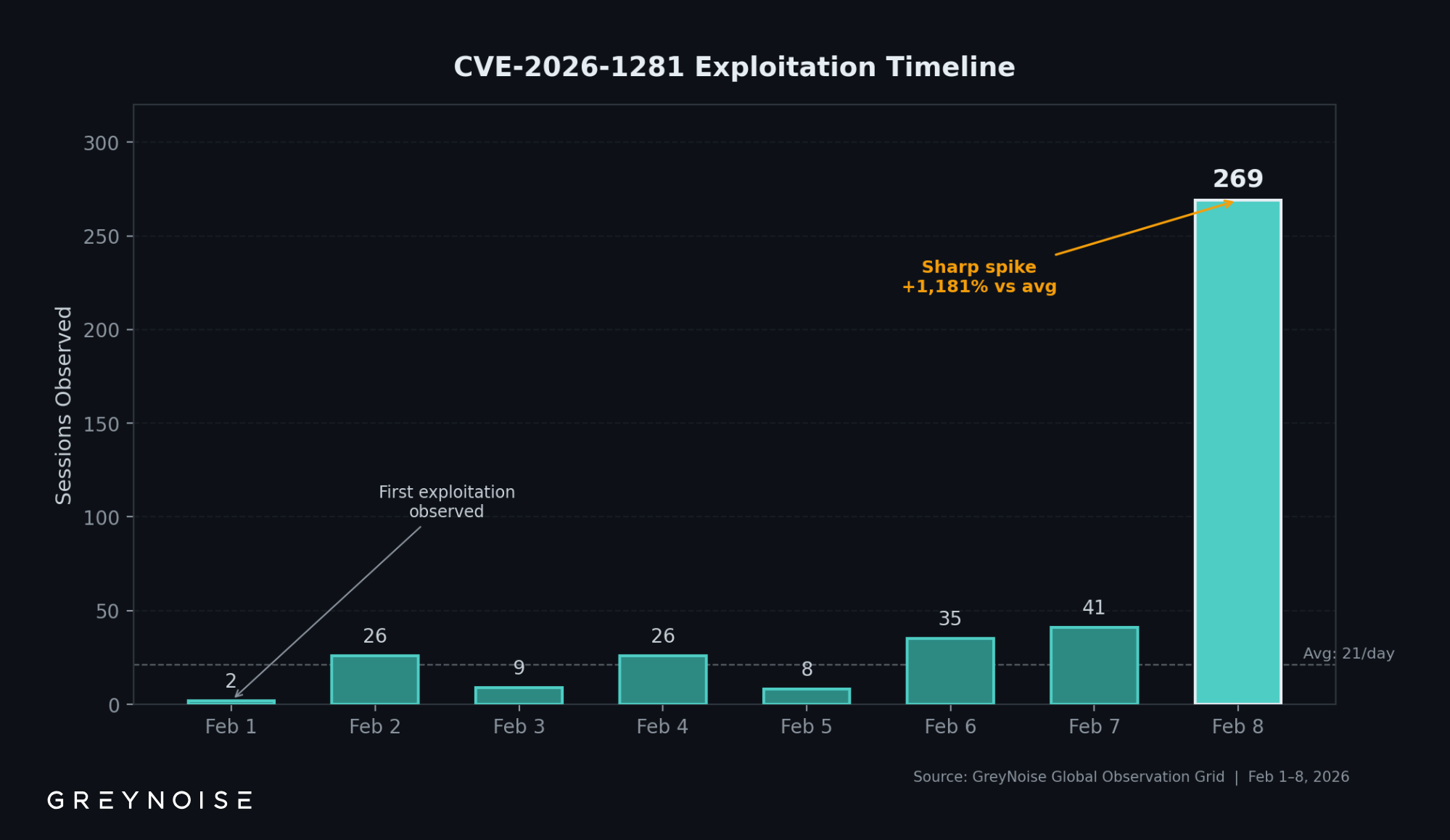

- Exploitation is accelerating. 269 sessions on February 8 alone, up from a daily average of 21. Defenders with unpatched, internet-facing EPMM instances should assume they have been scanned and investigate for signs of compromise.

For GreyNoise customers: An IOC package and executive situation report (SITREP) for CVE-2026-1281 have been delivered to your inbox. Check your email for the full package, including indicators, detection guidance, and a board-ready summary.

The Vulnerability and Timeline

CVE-2026-1281 is a CVSS 9.8 (v3.1) unauthenticated remote code execution vulnerability in Ivanti Endpoint Manager Mobile. It exploits Bash arithmetic expansion in EPMM’s file delivery mechanism, allowing an unauthenticated attacker to execute arbitrary commands on the underlying server. Ivanti also disclosed CVE-2026-1340 (CVSS 9.8), a related code injection flaw in a different EPMM component.

On January 29, three things happened on the same day: Ivanti published its advisory, CISA added CVE-2026-1281 to the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalog with a three-day remediation deadline, and Dutch authorities later confirmed that the Dutch Data Protection Authority (AP) and the Council for the Judiciary (RVDR) had been compromised via Ivanti EPMM. By January 30, watchTowr Labs had published a full technical analysis, and proof-of-concept code appeared on GitHub shortly after. NHS England, CERT-EU, and NCSC-NL also issued advisories confirming active exploitation.

Vendor disclosure, CISA KEV listing, and confirmed government compromise occurred on a single day. By the time most organizations saw the advisory, exploitation was already underway against real targets.

What GreyNoise Sensors Observed

GreyNoise first detected CVE-2026-1281 exploitation attempts on February 1, three days after disclosure. Between February 1 and February 9, GreyNoise sensors recorded 417 exploitation sessions from 8 unique source IPs.

The February 8 spike is notable: 269 sessions in a single day, roughly 13 times the daily average of the preceding week. This pattern of sustained low-level activity followed by a sharp escalation suggests either expanded targeting scope or retooling by the primary source.

The 8 Source IPs

IP geolocation reflects infrastructure registration, not operator location. GreyNoise is not attributing this activity to a specific threat actor.

The Dominant Source: PROSPERO OOO

One IP generated 346 of 417 observed exploitation sessions. 193[.]24[.]123[.]42, registered to PROSPERO OOO (AS200593) and geolocating to Saint Petersburg, Russia, accounts for 83% of all Ivanti EPMM exploitation in GreyNoise telemetry. Censys identifies this autonomous system with a confidence-scored "BULLETPROOF" label.

This IP does not appear on the widely circulated IOC lists for this campaign.

A Multi-CVE Exploitation Platform

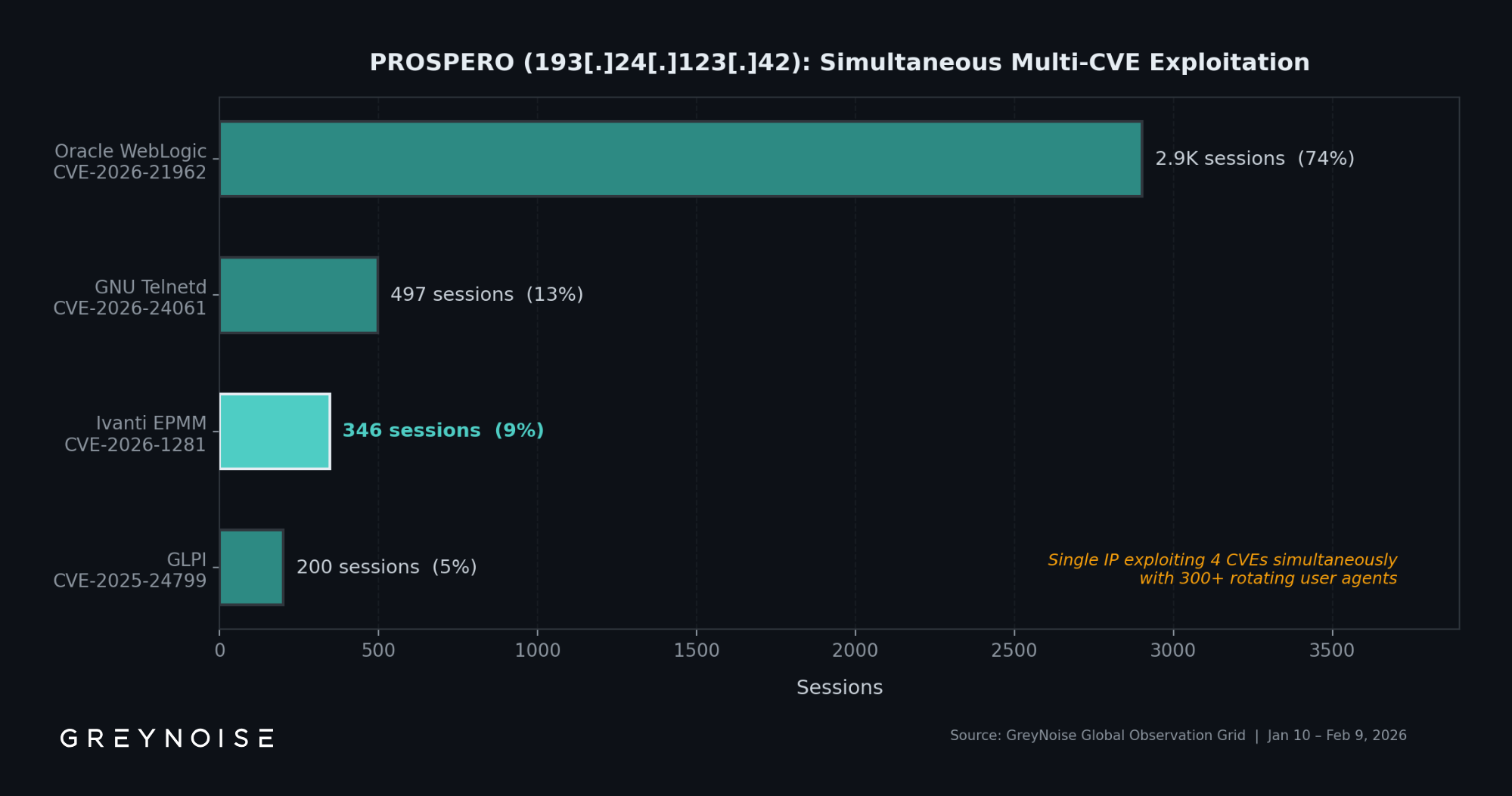

This is not a single-purpose host. GreyNoise telemetry shows 193[.]24[.]123[.]42 simultaneously exploiting four different CVEs across unrelated software:

The IP rotates through 300+ unique user agent strings spanning Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and multiple operating system variants. This fingerprint diversity, combined with concurrent exploitation of four unrelated software products, is consistent with automated tooling.

For additional context: Trustwave SpiderLabs has previously documented connections between PROSPERO and the Proton66 network (AS198953), linking both to bulletproof hosting services marketed on Russian-language cybercrime forums under the BEARHOST brand. That network has been associated with distribution infrastructure for GootLoader, SpyNote, and other malware families. This does not confirm attribution of the Ivanti campaign to any specific threat actor, but it places the dominant exploitation source on infrastructure with a documented history of hosting malicious operations.

85% of Exploitation Uses Blind RCE Verification

Of 417 exploitation sessions, 354 (85%) triggered GreyNoise’s out-of-band application security testing (OAST) interaction domain detection. The payloads instruct the target to generate a DNS callback to a unique subdomain, a technique that confirms command execution without requiring a direct response back to the attacker.

Because GreyNoise can observe not just that exploitation was attempted, but what the payload does when it runs, we see a clear pattern. In this case, 85% of payloads do one thing: phone home via DNS to confirm "this target is exploitable." They do not deploy malware. They do not exfiltrate data. They verify access.

That pattern is significant. OAST callbacks indicate the campaign is cataloging which targets are vulnerable rather than deploying payloads immediately. This is consistent with initial access operations that verify exploitability first and deploy follow-on tooling later.

What Happens After: The 403.jsp Sleeper Shells

External research corroborates this interpretation. On February 9, Defused Cyber reported a campaign deploying dormant in-memory Java class loaders to compromised EPMM instances at the path /mifs/403.jsp. The implants require a specific trigger parameter to activate, and no follow-on exploitation was observed at the time of their report. Defused Cyber assessed this as consistent with initial access broker tradecraft: establish a foothold, then sell or hand off access later.

The GreyNoise OAST data and the Defused Cyber findings point in the same direction. The exploitation GreyNoise observes is focused on cataloging and staging access, not on immediate deployment. For defenders, this means compromised systems may appear unaffected right now. The sleeper shells are designed to wait.

Note: The OAST patterns described above reflect what GreyNoise sensors observed. The Defused Cyber findings describe activity on production systems. Both datasets point in the same direction but represent different vantage points on the campaign.

Published IOCs in GreyNoise Data

Several widely published IOCs for this campaign do not appear in Ivanti EPMM exploitation attempts observed by GreyNoise sensors. GreyNoise does observe activity from these IPs, but targeting different vulnerabilities entirely.

Windscribe VPN Exit Nodes (185[.]212[.]171[.]0/24)

Four published IOC IPs (.151, .156, .137, .134) sit in a /24 block on M247 infrastructure (AS9009) in Amsterdam. Censys shows this block contains 95 hosts: a dense cluster of commercial VPN exit nodes, including Windscribe IKE endpoints with certificates carrying anti-censorship domain names.

In GreyNoise data, 99% of this subnet’s traffic targets Oracle WebLogic on TCP port 7001. It does not target Ivanti EPMM.

All four IOC IPs appear to be “dark” exit nodes: Censys detects zero inbound services on any of them. They exist to funnel outbound VPN traffic. Two of the four (.137, .134) have zero sessions in GreyNoise over the past 30 days.

This matters because these are shared VPN exits used by many subscribers for many purposes. The WebLogic scanning GreyNoise observes from this range may originate from a different VPN user than the Ivanti-related activity that prompted the original IOC listing. Blocking these IPs is a defensible decision, but defenders should understand that these indicators carry higher false-positive risk than dedicated exploitation infrastructure.

Separately, on February 5, Dutch authorities seized a Windscribe VPN server in the Netherlands as part of an undisclosed investigation. Windscribe disclosed the seizure, noting that its RAM-only (diskless) server architecture means no user data would be recoverable. No public reporting has linked the seizure to the Ivanti EPMM campaign.

A Compromised Residential Router (151[.]177[.]78[.]0)

One published IOC IP has never appeared in GreyNoise telemetry. Censys identifies 151[.]177[.]78[.]0 as an ASUS router on Tele2 residential broadband in Gothenburg, Sweden, running outdated firmware with an exposed cloud management interface and a factory-default certificate.

Its absence from GreyNoise data is itself informative. GreyNoise operates 5,000+ sensors across 80+ countries that observe internet-wide scanning and exploitation. An IP conducting broad exploitation would almost certainly appear. Zero sessions suggest this IP was used exclusively for targeted activity directed at specific systems, consistent with compromised residential infrastructure being used as an exit proxy.

For defenders who implemented the published IOCs: if you blocked the Windscribe VPN range (185[.]212[.]171[.]0/24) but not AS200593 (PROSPERO), your defenses may have addressed secondary infrastructure while missing the primary exploitation source in GreyNoise telemetry.

Strategic Implications

IOC-based defenses face a fundamental confidence problem in this campaign. Published indicators ranged from shared VPN infrastructure (low confidence, high false-positive risk) to bulletproof hosting with concentrated exploitation activity (high confidence, low collateral). Organizations applying uniform blocklist policies to all published IOCs are either over-blocking legitimate traffic or under-blocking actual threats. The 83% concentration on a single PROSPERO-hosted IP, while published IOCs showed zero overlap with GreyNoise exploitation data, demonstrates that post-incident IOC sharing can miss the infrastructure actually used at volume. Defenders benefit from a confidence-scoring framework for IOCs that accounts for infrastructure type, observed behavior concentration, and temporal proximity to the vulnerability window.

The OAST callback pattern and the Defused Cyber sleeper shell findings together suggest that initial exploitation is only the first phase. If this campaign follows the initial access broker model, compromised EPMM instances may not show obvious signs of abuse for weeks or months. Organizations that patched quickly but did not investigate for prior compromise during the exposure window may have dormant implants in their environment. The absence of visible post-exploitation activity is not evidence of safety.

Mobile device management platforms represent a target class with compounding risk. EPMM compromise provides access to device management infrastructure for entire organizations, creating a lateral movement platform that bypasses traditional network segmentation. Organizations running MDM platforms should treat these systems with the same criticality as domain controllers or identity providers, including network isolation, aggressive patch cycles, and monitoring for unauthorized configuration changes or device enrollments.

The exploitation timeline has compressed below the threshold of conventional patch management. Same-day government compromise and a 72-hour gap to widespread scanning leaves no buffer for "patch this weekend" strategies. Organizations with internet-facing MDM, VPN concentrators, or other remote access infrastructure should operate under the assumption that critical vulnerabilities face exploitation within hours of disclosure.

Recommendations

For Security Leadership:

- Audit whether Ivanti EPMM and other MDM infrastructure is directly internet-facing. MDM platforms manage entire device fleets; their compromise exposure is disproportionate to a single server. Consider placing MDM behind VPN or zero-trust network access.

- Evaluate your IOC ingestion workflow. Are indicators enriched with infrastructure context before being added to blocklists? The difference between a bulletproof hosting IP and a shared VPN exit node is the difference between a high-confidence block and a potential false positive.

- If your EPMM instance was internet-facing and unpatched between January 29 and your patch date, commission an investigation. The sleeper shell tradecraft observed in this campaign means compromise may not be visible through normal monitoring.

For Security Operations:

- Block AS200593 (PROSPERO OOO) at the network perimeter. This autonomous system accounts for 83% of observed Ivanti EPMM exploitation and carries a Censys BULLETPROOF designation. GreyNoise dynamic blocklists can help maintain coverage as exploitation infrastructure shifts.

- Review DNS logs for OAST-pattern callbacks: unique, high-entropy subdomains resolving to known OAST interaction infrastructure. These indicate that exploitation payloads executed on your systems.

- Monitor for the /mifs/403.jsp path on EPMM instances. This is the sleeper shell location identified by Defused Cyber. Its presence indicates compromise even if no further malicious activity is visible.

- Consider restarting EPMM application servers to clear in-memory implants that may have been staged. In-memory class loaders do not survive a process restart.

For Ivanti EPMM Administrators:

- Apply patches for CVE-2026-1281 and CVE-2026-1340 immediately. Exploitation is active and accelerating.

- If your instance was unpatched and internet-facing at any point between January 29 and your patch date, investigate for indicators of compromise: unexpected files at /mifs/403.jsp, anomalous outbound DNS activity, unfamiliar Java processes, and any evidence of unauthorized administrative actions on managed devices.

- Review whether EPMM needs to accept connections from the open internet. Where architecturally feasible, restrict access to known network ranges or require VPN authentication before reaching the EPMM interface.

View real-time exploitation data: Ivanti Endpoint Manager Mobile Code Injection CVE-2026-1281 RCE Attempt

Full fingerprint analysis and session-level exploitation data available to GreyNoise customers.

.png)

.png)